The Headless Gunman

How AI 'upscaling' tools - and the demand for high-resolution imagery - have given rise to a new form of misinformation.

There’s a photo circulating on social media at the moment which seems to highlight America’s descent into fascism. It depicts the moment protestor Alex Pretti was shot and killed by US Border Patrol agents in Minneapolis. Like the famous image of Jeffrey Miller who was gunned down on the campus of Ohio’s Kent State University while protesting the war in Vietnam the image of Alex Pretti’s murder has resonated with many Americans. It shows Pretti on his knees flanked by three masked men in paramilitary gear – one of whom is pointing a gun at the back of Pretti’s head. It’s a chilling illustration of the brutality employed by police and immigration officers carrying out Trump’s crackdown on ‘Sanctuary Cities’ like Minneapolis.

The problem with the image is that it’s also, quite literally, an illustration.

This is not immediately apparent because the image has all the hallmarks of an actual photo. It has the resolution you would expect of a photo. It has the shallow focus that suggests it was taken with a telephoto lens and it has all the detail you’d expect to find in a real photograph. You can see the zip on Pretti’s hoodie, you can count the magazine pouches on the chest rigs worn by the Border Patrol agents and you can clearly see a wedding ring on the gunman’s left hand. If you squint you can almost make out the badge on the parked car in the background.

The problem is that none of these details are real. They’re digital artefacts generated in the absence of visual data because the actual killing was recorded from a distance with a camera phone.

So where did this image come from? Well, presumably, at some point between the shooting and the groundswell of outrage that followed, someone took a still frame from the original video, ran it through an AI-upscaling tool and published the results without explaining what they’d done. That image quickly went viral and a bunch of people on Twitter and other social media platforms (some of whom should know better) presented it as documentary evidence of what occurred.

In reality Pretti’s hoodie didn’t have a zip, the Border Patrol agents weren’t carrying hundreds of rounds of spare ammunition and there’s no way of knowing if the gunman was married because his left hand isn’t even visible in the original frame. A closer look at the image reveals even more glaring problems. Most notably one of the Border Patrol Agents is missing his head and his right arm appears to merge back into his torso while his right leg transitions into some sort of metal contraption. Likewise the beanie worn by the agent with the gun has a weird right-angle in the headband and the weapon carried by the agent behind him is less a firearm than a collage of vaguely firearm-shaped elements. On closer inspection all the apparent details of the image turn out to be small pieces of one big hallucinatory mess.

Most troubling of all the AI-upscaling process has transformed the phone in Pretti’s right hand into some amorphous black object – feeding into a narrative peddled by the White House that Pretti was brandishing a weapon when he was killed. Despite all these bizarre elements thousands of people circulated the image in the hopes of identifying the gunman. But that request was only ever going to yield false positives because the face in the image does not belong to a real person. A similar demand for justice followed the killing of fellow Minneapolis resident Renee Good. In the aftermath of that shooting Twitter users attempted to digitally ‘unmask’ one of the assailants using the app’s built-in chatbot. ‘Grok’ obligingly provided a photorealistic impression what the police officer might look like without his face-covering but, once again, very few users seemed to realise that this image was fundamentally unreliable*.

Having to point out that images like these are bullshit is particularly frustrating because there are already people making bad-faith accusations of ‘fake news’ to discredit evidence of police brutality. The upscaled image of Pretti and the unmasked image of the ICE officer both appear to have been made by people justifiably angry over the murder of their fellow citizens. And while I can appreciate the urge to create an image that mobilises people to take action I can’t understand why anyone would want to undermine the legitimacy of the original recording in order to get that message across. Because in order to wring a little more public outrage from this latest killing the author of the upscaled image has further discredited the idea of photography as a forensic medium.

That said, it’s possible that the person who created this image didn’t actually understand what they were doing. It’s possible they didn’t notice the headless police officer and the Picasso beanie and assumed that the resulting image was just a ‘zoomed in’ version of the original still frame. After all, decades of sci-fi TV shows and movies have told us that this sort of image enhancement is possible.

But it isn’t. The data you capture when you press record on a camera or a smartphone is all the data you’ll ever have.

But there’s bound to be a degree of confusion about this – not only because of sci-fi police procedurals but because tech companies have spent years advertising software which promises users the ability to do just what Deckard did with his Polaroid in Blade Runner. The reality of this technology, by comparison, is far more prosaic. For many years these applications used a mathematical process called interpolation which separates the existing pixel data into a larger grid and then ‘estimates’ the pixel values for the spaces in-between. This process does, technically, generate a higher resolution image but it does so at the cost of fine-grain detail – producing a weird glossy effect.

In the last few years, however, software providers have pivoted to using generative AI models to fabricate a much more detailed version of the image you’ve uploaded. These algorithms draw from a database of hundreds of thousands of similar photos and then shoe-horn their output into the rough outline provided by the original image.

You can see examples of these two methods of ‘upscaling’ in a recent post on Stack Exchange. Responding to a question about how these techniques differ photographer Steven Kersting provided an object lesson in the shortcomings of generative AI. To demonstrate the technology he used a photo he’d previously taken of an owl in flight where the camera’s shutter speed had been a fraction too slow. What he ended up with was a profile of slightly blurry owl. Amassing an enormous collection of blurry bird photos is an occupational hazard for any wildlife photographer but, until recently, there wasn’t much you could do to salvage those images.

Enter Gigapixel – a photoshop plugin devised by U.S. tech company Topaz Labs. For $12 USD a month Topaz Labs promises to ‘super-scale’ your image by creating new pixels out of thin air. They also boast that their application can correct blurry or out-of-focus images.

In his post on Stack Exchange Kersting posted the results of his first attempt to correct the motion blur. This method employed a well-established mathmatical process know as deconvolution which tries to calculate – and reverse – the path taken by the light as it moves across the image sensor at the moment of exposure. In addition Kersting also had the app double the resolution of the original image using an interpolation model. The resulting image is surprisingly sharp and very difficult to fault.

By way of comparison Kersting then showed what the plugin produced when he asked it to correct the blur and upscale the image using generative AI. This time it replaced Hedwig with the sort of creature you find in medieval marginalia – an owl with cat’s eyes, whiskers and a nose instead of a beak. If that seems like a bizarre result you have to understand that these applications rely on statistical models trained on a vast quantity of publicly available images and there are a lot more pictures of cats on the internet than there are pictures of owls. Presumably the algorithm detected round yellow eyes and striations and went ahead and filled the profile of the owl with the features of a cat.

The take-home lesson from this experiment is that when you use generative AI to ‘upscale’ a photo you’re not just smearing and sharpening the existing image data, you’re actually replacing it with an amalgamation of all the images that resemble the original scene.

As you might imagine there are lots of ways this can go wrong.

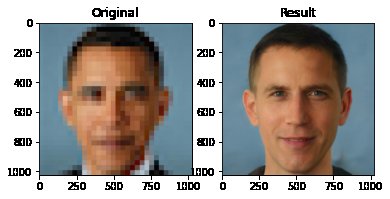

Kersting’s Cat/Owl chimera demonstrates that images produced by generative AI generally reflect whatever biases exist in the training data. This has been a flaw in these sorts of applications right from the start. When NVIDIA made its StyleGAN model available to the public in 2019 developers immediately began using it to build apps which promised to upscale low-resolution images. One of these apps, nicknamed PULSE, was heavily promoted on Twitter and, judging from the comments at the time, many users were amazed at its ability to turn vague, pixellated shapes into vivid, high-resolution portraits.

Others were more sceptical. In what passes for a famous tweet one user called @Chicken3gg revealed how the app had converted a low-res image of Barack Obama into a portrait of a generic, middle-aged white guy. Spiritually accurate but visually misleading.

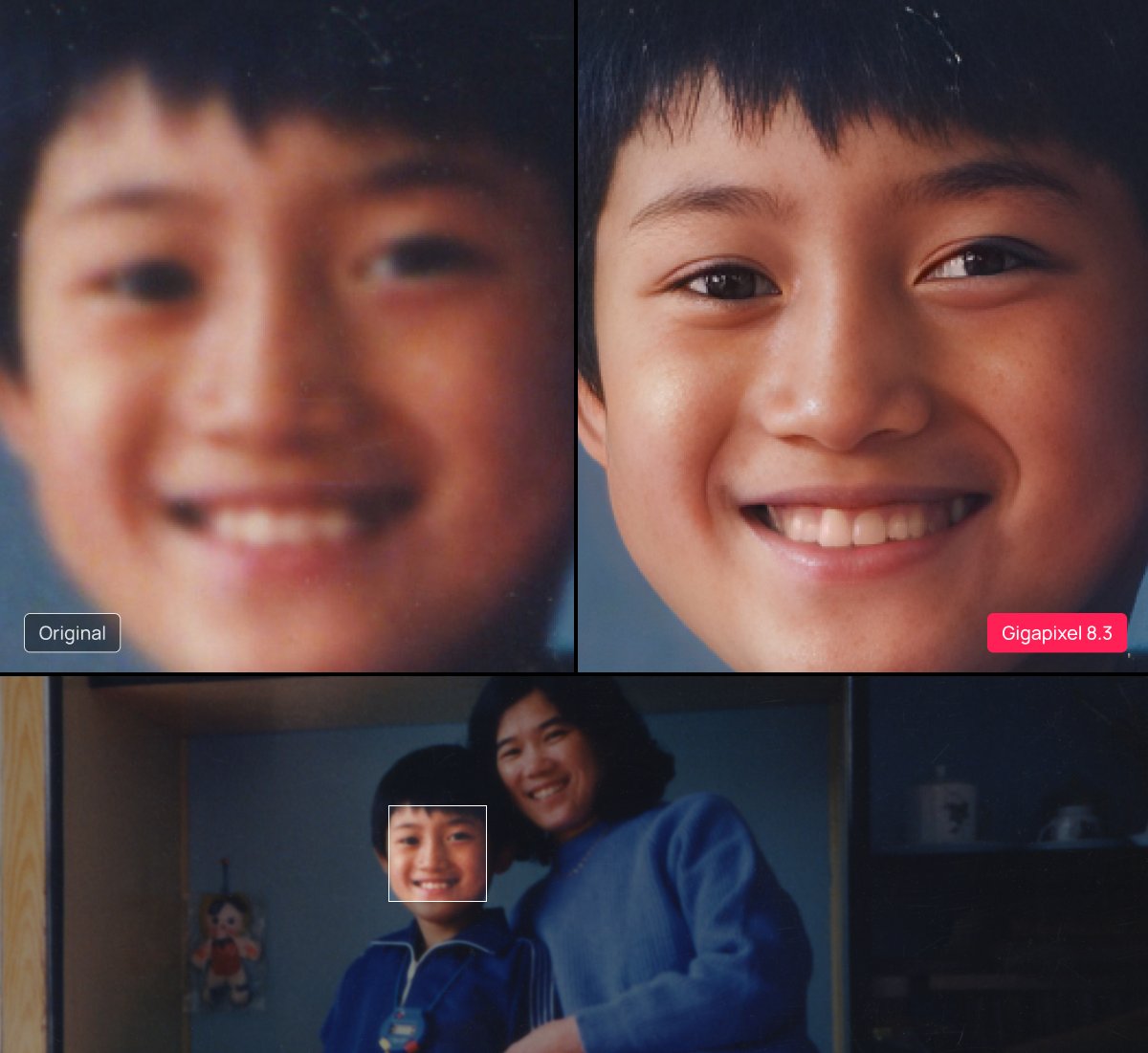

Last year, when Topaz Labs announced an update to their upscaling tool, they used a blurry photo of a mother and child to demonstrate their model’s ability to correct out-of-focus images. Their promotional post claimed that Gigapixel could isolate the child’s face and convert it into a clear, high-resolution portrait. Most of those who responded to this demonstration were suitably impressed but others smelled a rat. As one user pointed out:

“What makes you recognize someone are the near imperceptible differences in proportion, scale etc. You can’t just apply “averaged asian boy” to resolve data that isn’t there. It’s not a real person. You are creating false memories. You are adding psychosis to your surroundings.”

So biases in the training data are clearly a fundamental problem with this technology. The other problem is that generative AI tools are incapable of assigning any sort of ‘confidence score’ to their output. These systems are designed for statistical pattern matching rather than analysis – which means they’ll never come back with an error when a prompt sends them into uncharted territory. In the case of upscaling tools like Topaz’s Gigapixel the underlying model has no way to assess the quality of the visual information it has been given and, in the absence of any legible data, these models will stubbornly continue to fill in the blanks with whatever pixels seem statistically plausible – producing Cronenberg monstrosities like the headless Border Patrol agent.

The most vocal cheerleaders for generative AI refer to these surrealist elements as ‘hallucinations’. They insist that generative AI is still in its infancy and, with enough additional training data, these models will eventually be able to produce flawless results. Given recent improvements in Gen-AI output this argument sounds plausible. After all, early image models produced mutant people with eight digits on one hand and twice too many teeth while the latest generation models often produce portraits of fake humans that are almost indistinguishable from real photos.

But this assumption of steady improvement rests on a fundamental misunderstanding of how these models work.

Hallucinations will always occur because runaway patterns and weird substitutions aren’t glitches in a program that otherwise generates realistic images – they’re the mechanism by which those images are generated in the first place. When it comes to generative AI it’s hallucination all the way down.

The problem we all face right now is that tech companies have spent hundreds of millions of dollars over the last few years telling people that their chatbots are sentient and that AI-upscaling tools can conjure up details that your camera never even recorded. This PR blitz has overwhelmed all attempts to provide the general public with a baseline level of AI literacy. So now we have people thinking that they can buy photoshop plugins that will let them count the hairs on Che Guevara’s moustache.

Anyway, now you know the truth. And, as G.I. Joe always said, knowing is half the battle. So keep an eye out for headless gunmen and don’t be afraid to call out anyone who tries to turn low resolution photos into high resolution bullshit.

*The same upscaling techniques were applied to grainy CCTV footage of man suspected of murdering right-wing troll Charlie Kirk. Once again the faces generated by those tools did not resemble the actual suspect.

Leave a Reply