Searching for Cyrus: Part II

The search continues through the the streets of Shiraz and the ruins of Persepolis.

After a few days in Tehran we travelled south in a sleeper carriage about a thousand kilometres to the beautiful city of Shiraz which lies at the edge of Iran’s Zagros Mountain Range. For many centuries the region had been renowned for its vineyards and its namesake red wines. The Islamic conquests of the 7th century put a dent in the wine market but the industry carried on right up until the 1979 revolution when longstanding Islamic prohibitions on alcohol were tightened. These days the regional economy is focused on assembling electronics and refining crude oil. While the Iranian economy lumbers on despite setbacks and sanctions the unemployment rate amongst the youth remains uncomfortably high. At our guesthouse we were met by Mahsa who drove a souped-up Peugeot with a fancy aftermarket sound system. She spoke longingly about her cousins in Manchester, Toronto and other foreign cities. She also had plans to emigrate but passport applications are subject to lengthy bureaucratic processes and anyone suspected of being critical of the government or the religious authorities can be blacklisted from travelling abroad.

Iranian men are obliged to spend four years in the army before they can even apply for a passport which costs quite a bit of money and is subject to several layers of approval. For those determined to leave the country these obstacles can be daunting and yet everywhere we went in Iran we met young people who were saving money, applying for student visas or preparing to covertly make their getaway. It’s easy to assume that Iran’s religious authorities would consider the emigration of disgruntled citizens a win-win scenario. The dissidents get to leave and the authorities get to govern a less restless population. But the sheer number of people that want to leave means that loosening travel restrictions could lead to a mass exodus- crippling the Iranian economy. And yet despite all the hurdles that the Islamic Republic places in front of would-be emigres Iran’s brain drain continues apace.

Those who don’t have the money or the connections to get a working visa or a place at a foreign university are forced to make desperate journeys across neighbouring countries to find somewhere they can safely settle. What’s often left out of the debate over punitive refugee policies in countries like Australia is how neatly they dovetail with the punitive condition imposed by the regimes from which those people have fled. The young woman that Amy and I stayed with in Isfahan was particularly dismayed by how the Australian government had treated Iranian/Kurdish refugee Behrouz Boochani. Why, she asked, had he been imprisoned and tortured for so many years on Manus island? What had he done to deserve that sort of treatment? It was a good question and one that I didn’t have a good answer for. I could have told the story of our former Prime Minister John Howard, and the hysteria he whipped up following the interception of a container ship carrying refugees in 2000. I could have tried to explain how, following that incident, our two major political parties basically competed with one another to punish refugees for attempting to reach our shores but that wouldn’t have really answered the question. All I could say was that our country was deeply racist and that our refugee policy was simply the starkest reflection of that.

The main streets of Shiraz (like most Iranian cities) are lined with faded banners and murals depicting the ‘martyrs’ of the revolution – young men killed in the eight-year war with Iraq. The conflict started with an invasion by Iraq in 1980 – less than a year after the revolution had brought Ayatollah Khomeini to power. The border between the two nations had been disputed for a long time but there hadn’t been any major attempts by either side to settle the issue. In 1980 Iraqi president Saddam Hussein took advantage of the political turmoil in Iran to mount an invasion. Saddam assumed that a destabilised Iran wouldn’t put up much of a fight. Instead, the invasion prompted millions of Iranians to rally behind the new Islamic Republic – even those who hadn’t been enthusiastic supporters of the new regime. Iran’s newly minted ‘Supreme Leader’ Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini portrayed the conflict as an existential war of survival for the Shia faith and Iranian state media made comparisons between the Iraqi invasion and the battle of Karbala in the 7th century that led to the Sunni/Shia split.

A great surge in nationalism and religious fervour allowed the Iranians to halt the invasion and then push the Iraqi army back beyond the original border. Two years into the war Iraq had lost all the territory it had originally captured and yet neither side had managed to gain a decisive advantage over the other. Over the following six years the war lapsed into a brutal stalemate at the border while both sides bombarded each other’s major cities with missiles. During those dark days the Iranian army also employed human wave attacks comprised of teenage volunteers inspired by the promise of martyrdom. Thousands of these young men were killed in futile frontal assaults on Iraqi positions. during the war the U.S. government officially backed Saddam but covertly sold weapons to Iran. On July 3rd 1988, as the war was drawing to a close, a U.S. frigate stationed in the Persian Gulf mistakenly shot down an Iranian airliner, killing all 290 passengers onboard.

Ultimately the war claimed more than a million lives and the massive debt incurred by Iraq set the stage for Saddam’s subsequent invasion of Kuwait. Ever since the war ended the portraits and names of those killed have been the bedrock of the Islamic Republic’s propaganda efforts. The images themselves are often scans of unsmiling ID-card portraits and these faded mugshots of dead teenagers follow you wherever you go.

Keeping the memory of the martyrs alive remains a high priority for the Islamic Republic but the methods used to do so are sometimes a little hit and miss. Not long after we arrived in Shiraz we saw a cheerful old man on roller blades with an Iranian flag strapped to his back blaring music from a bluetooth speaker. Later on we were told that he was paid by the government to skate around town playing revolutionary songs. Which sounds like a good gig if you can get it but does seem like a desperate strategy from a propaganda perspective

In Shiraz we visited the city’s premiere tourist attraction – The Nasir-ol-Molk Mosque – where tens of thousands of people go each year to get nice rose-tinted instagram selfies. The stained glass and the tiling work was certainly beautiful but I couldn’t help feeling that the ‘Pink Mosque’ mainly served as a sort of decoy so that tourists wouldn’t bother residents attending the city’s actual places of worship. In the sunlit prayer hall I watched tourists jockey for the best position in front of the stained glass. Meanwhile, in the reflective pond, I watched another feeding frenzy take place as several starving goldfish finished off one of their weaker companions. Later on that day we managed to arrange a brief tour of an actual mosque which was less kaleidoscopic in terms of its decor but much more interesting as a glimpse of day-to-day life.

After a day spent sheltering from the heat in Shiraz we arranged a tour of Persepolis. Our guide to the ancient capital was Peyman Soodmand (instagram handle: @MrPersepolis) a stylish young Iranian who worked as a tour guide and spent what he earned travelling the world. Peyman himself belonged to a sect of Islam known as Sufism which is sits awkwardly between the main streams of Sunni and Shia Islam. The Sufi tradition is at least as old as those other sects but, rather than being concerned with a particular line of Imams, Sufism emphasises personal piety and spiritualism. The way Peyman described it – as a way of life guided by a mentor – sounded more like becoming a Jedi1.

Understandably Peyman had a bit of a chip on his shoulder when it came to how Iran’s ancient history has been represented in the West. After all, the most popular depiction of the Achaemenid Empire to come out of Hollywood in recent years has been Zack Snyder’s 300 – a mythic retelling of the Battle of Thermopylae based on a graphic novel by Frank Miller. In Snyder’s film adaptation the Emperor Xerxes is presented as a hairless nine-foot demigod, dripping in gold piercings and dressed like he’s on his way to an S&M club. Like a lot of popular history 300 presented the Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC as a decisive turning point in some mythic contest between Persian Tyranny and Greek Democracy – conveniently ignoring the fact that Sparta at the time was a slave state where woebegotten helots – who had a social status roughly equivalent to that of a feral dog – outnumbered Spartan citizens seven to one.

Peyman was happy to have the opportunity to set the record straight2. He characterised the Achaemenid era as a golden age that produced all sorts of social and technical innovations. Indeed the Achaemenids were the first Empire to set up a functioning postal system and Persian aqueducts pre-date the first Roman watercourses by several centuries. Persian sculptures and jewellery from this period are highly prized by collectors and Peyman took a wistful sort of pride in the fact that many of those artefacts have pride of place in museums across the Western world. As we approached the ruins of the ancient capital he laid out the scale of the Achaemenid Empire under Darius the Great and the religious tolerance that kept the Empire stable over so many generations.

Perhaps the most crucial piece of evidence for that tolerance is a proclamation recorded on a clay cylinder by the founder of the Achaemenid empire – Cyrus The Great. The text – written in Akkadian cuneiform – describes Cyrus as a benevolent ruler who has graciously decided to repatriate various groups who’d been uprooted and exiled by the former rulers of Babylon. It also proclaims that their temples and cult sanctuaries will be restored re-consecrated. The original cylinder is on display at the British Museum but, on a couple of occasions, it has been loaned back to Iran. During the reign of the last Shah of Iran – Mohammad Reza Pahlavi – the cylinder was held up as an early charter of human rights but most scholars of Ancient Persia consider that to be a bit of an overstatement. Nevertheless one former director of the British Museum, Neil MacGregor, acknowledged that Cyrus’ edict was evidence of “a new kind of statecraft” in that it represented “the first attempt we know about [of] running a society, a state with different nationalities and faiths”.

Over the years many Jewish scholars have used the ‘Cyrus Cylinder’ to corroborate the story told in the biblical Book of Ezra which describes the return of the exiled Jewish population to Judea. The early Hebrew sources credit Cyrus for this turn of events so, naturally, he gets praised as a just and wise ruler. The Ancient Greek sources, on the other hand, are less enthusiastic about Cyrus and his legacy. The city-states of Ancient Greece occupied a very small frontier of the sprawling Persian Empire and, while the Persians were renowned for buying the allegiance of their neighbours, they favoured the stick rather than the carrot when it came to the Greeks. In 492 B.C. the Persian Emperor Darius I (AKA Darius the Great) ordered an invasion of Greece as punishment for the support that Athens had lent to an earlier Ionian Revolt. The Persian invasion was thwarted by the Athenians at the Battle of Marathon but Darius’ successor, Xerxes I, launched another punitive expedition only a few years later and succeeded in destroying many Greek cities, including Athens. Given the bad blood involved, any praise for the founder of the Achaemenids in Greek sources is usually grudging at best. The exception to this is Xenophon’s biography of Cyrus, The Cyropaedia, which presents Cyrus as a benevolent dictator:

“[He] was able to penetrate that vast extent of country by the sheer terror of his personality that the inhabitants were prostrate before him…and yet he was able at the same time, to inspire them all with so deep a desire to please him and win his favour that all they asked was to be guided by his judgment and his alone…Thus he knit to himself a complex of nationalities so vast that it would have taxed a man’s endurance merely to traverse his empire in any one direction.”

Likewise it’s hard not be impressed by the scale of the ruins at Persepolis. Commissioned by Darius sometime in the 6th century B.C., Persepolis occupies an area of about 125,000 square meters but, despite its size, the complex was never actually intended to serve as a functioning city. Rather it was one of several administrative and ceremonial palaces used by the Achaemenid rulers. Think of it as the Mar-a-Lago of ancient Persia. According to archeologists Persepolis was mainly used to celebrate the festival of Nowruz – during which time the rulers of all of the subject nations of the Empire were summoned to pay tribute to the ‘Shah of Shahs’.

Persepolis stood for more than two centuries before it was razed by Alexander the Great in 330 BC. The exact sequence of events that led to the destruction of Persepolis is somewhat murky. According to most accounts Alexander torched the palace in a fit of anger after drinking one too many cups of wine. But, of course, the chroniclers of the time couldn’t resist finding a way to blame a woman for this act of cultural vandalism. According to those sources it was a courtesan named Thaïs who convinced Alexander to burn Persepolis in revenge for the destruction of the Acropolis by Xerxes a century and a half earlier. Writing in the first century BC the Greek historian Diodorus described the moment when Alexander’s victory celebrations really got out of hand.

“While they were feasting and the drinking was far advanced, as they began to be drunken a madness took possession of the minds of the intoxicated guests. At this point one of the women present, Thaïs by name and Attic by origin, said that for Alexander it would be the finest of all his feats in Asia if he joined them in a triumphal procession, set fire to the palaces, and permitted women’s hands in a minute to extinguish the famed accomplishments of the Persians. This was said to men who were still young and giddy with wine, and so, as would be expected, someone shouted out to form the comus and to light torches, and urged all to take vengeance for the destruction of the Greek temples. Others took up the cry and said that this was a deed worthy of Alexander alone. When the king had caught fire at their words, all leaped up from their couches and passed the word along to form a victory procession in honour of Dionysus. Promptly many torches were gathered. Female musicians were present at the banquet, so the king led them all out for the comus to the sound of voices and flutes and pipes, Thaïs the courtesan leading the whole performance. She was the first, after the king, to hurl her blazing torch into the palace. As the others all did the same, immediately the entire palace area was consumed, so great was the conflagration. It was remarkable that the impious act of Xerxes, king of the Persians, against the acropolis at Athens should have been repaid in kind after many years by one woman, a citizen of the land which had suffered it, and in sport” (XVII.72).

When we arrived at Persepolis we joined the crowds and followed Peyman up the wide staircase to the entrance of the palace complex – following the same route that representatives of the various kingdoms would have taken when they made their yearly trip to pay tribute to the Emperor. At the top of the stairs we found ourselves in the shadow of two enormous stone lamassu – mythical winged bulls with (once) human faces. These guardians were supposed to represent the power and authority of the Achaemenid royal family and, much like medieval gargoyles, their presence was believed to ward off evil. Our companion Matt, who is a dual American/Australian citizen and therefore part-hellspawn of The Great Satan, managed to pass through the gates without incident so their magic appears to have worn off. Having passed safely through the Gate of All Nations we entered the main courtyard outside the Apadana Palace and saw local tourists with VR headsets marvelling at what the city would have looked like in its original form.

For those without the benefit of computer-generated imagery it’s hard to envision the palace in its original glory4 but, thanks to some very meticulous restoration work, you see can still see where the various structures once stood. Nevertheless the site, as a whole, still looks fairly empty because most of the debris left behind following the destruction of the city was carted off and repurposed to build the nearby city of Estakhr – leaving only the heaviest and most well buried stonework behind for archeologists to examine. In the Palace of Hundred Columns only fourteen pillars have been reconstructed. Many of the decorative reliefs have also been deliberately defaced but others – like the polished reliefs on the foundations of the Apadana Palace – remained buried in the rubble for several centuries. Now that they’ve been uncovered they provide a wonderful snapshot of 6th century BC fashion.

The Apadana reliefs depict a procession of dignitaries who have to come to pay homage to Persia’s ‘king of kings’. Each group of figures represents a specific nation within the empire and each is recognisable by their clothing and their choice of gift. In one section you can see the Lydian envoys (who occupied the Aegean coast) in their fringed coats holding vases and cloth. Behind them are a pair of Armenians bringing wine to the Emperor while the Scythians bring horses and gold bracelets. The Thracians bring weaponry and the Libyans bring chariots and spears and horned goats. Between each set of supplicants are Persian guides – many of whom are walking hand-in-hand with their guests. Peyman clearly took pride in the fact that he was, in a sense, performing the same role, in the same place, two and half thousand years later.

Ethnic stereotypes would appear to be a longstanding artistic tradition and, as we moved along the relief, Peyman pointed out the ringlets on the hair of the Jewish envoys and the billowy pants of the Afghans and the pot-bellied, shirtless Indians. At the end of this procession sits the Emperor – thought to be Darius I – who sits on a throne flanked by his heir, Xerxes3. Both these figures are substantially taller than those bringing tribute. Stuffy historians and archeologists would no doubt say that this difference in height symbolises the Emperor’s exalted status but Zack Snyder knows it’s because the Emperor and his son were actually nine foot tall freaks of nature.

As we wandered through the ruins of Persepolis we came across school groups of various ages. Ancient history is a part of the school curriculum but it’s always been an awkward subject for the revolutionary regime. The Islamic Republic’s Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution dictates the content of Iran’s history curriculum and they generally characterise pre-islamic Iran as a dusty historical backwater entirely divorced from the modern state and lacking any ideas worth emulating. This conception of pre-Islamic Iran as ‘negative heritage’ is partly a reaction to the nationalist ideology promoted by the former Shah of Iran – Mohammad Reza Pahlavi – who had celebrated the achievements of Ancient Persia above everything else that followed.

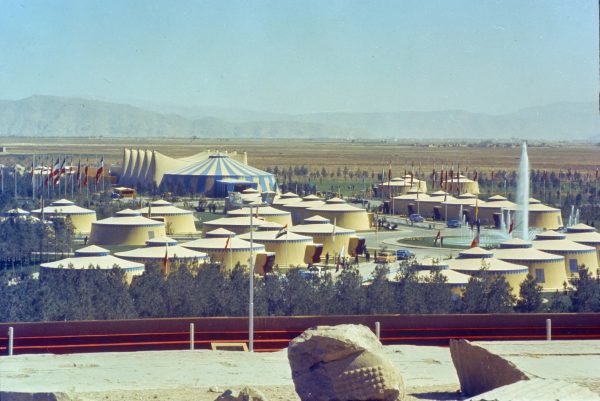

In fact, right beside the ruins at Persepolis you can find a testament to Pahlavi’s attempts to revive the glory of the Achaemenid dynasty. A few hundred meters from the turning circle where the tour buses stop there’s a big plaza surrounded by fir trees. Five wide avenues radiate out from what was once a spectacular central fountain and, beside each avenue, are the skeletal remains of a tent city erected to celebrate the 2500th anniversary of the Persian Empire. What the Shah referred to as ‘the biggest party on earth’ took place over three days in October, 1971. Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie was the guest of honour but hundreds of other royals, heads of state and foreign dignitaries also attended. Even Australia’s Governor General at the time, Sir Paul Hasluck, received an invite.

Planning for the event had begun years earlier. A small forrest was planted to make the windswept plains around the ruins more hospitable and this new parkland was populated with thousands of exotic songbirds (most of which did not survive Iran’s summer). The Shah had a new airport constructed about 30 kilometres from the ruins to spare his guests the nine-hour trip from Tehran. The tents – each outfitted with plumbing, electricity and air conditioning – took a year to build and consumed 37 square kilometres of silk. In addition each guest received a hand woven silk portrait of themselves to take home. The festivities included a parade of 1,800 costumed soldiers riding horses and camels.

When it came to catering for the event, the Shah spared no expense. Eighteen tons of food – including 150kg of Beluga caviar – were flown in alongside thousands of bottles of champagne and brandy imported from Paris. To immortalise the party the Shah commissioned a suitably pompous documentary narrated by Orson Welles but the footage doesn’t quite mange to convey the majesty of the occasion. Although often described as the height of luxury the decor inside the banquet hall still looks a little chintzy to modern eyes. Less Vanity Fair, more Franco Cozzo.

Allegedly the party ended up costing close to a billion dollars – setting a record that stood until last year when India’s richest man bankrolled a ridiculous months-long celebration for his son’s wedding.

I say ‘allegedly’ because the Shah’s opponents were more than happy to inflate the price of this lavish ceremony in order to portray the Iranian king as a corrupt dictator who had become drunk on power. For his part the Shah believed that the best way to restore Iran’s national pride was by reconnecting the modern state with its ancient past. To open the festivities the shah led a procession of military and government officials to the tomb of Cyrus The Great. In his speech the self-proclaimed Shahanshah, King of Kings, Light of the Aryans, Shadow of the Almighty, paid homage to Cyrus:

“Cyrus! Great King, King of Kings … you immortal Hero of History, father of the world’s most ancient empire, great liberator of all time, worthy son of mankind. … After 2500 years, the Persian flag waves as proudly as in your era of glory. … Today, as in your day, Persia bears the message of liberty and love of mankind in a troubled world … Cyrus, Great King, King of Kings…, you may rest in peace, for we are vigilant and will remain so forever.”

This spectacle at Persepolis took place amid an economic boom in Iran but the new wealth generated by high oil prices and lucrative trade deals was taking time to trickle down and many Iranians living in rural areas were still desperately poor. By the mid 1970s the Shah’s ambitious plans to modernise and industrialise Iran’s economy had begun to show results but the massive sums of money spent on the festivities still outraged many Iranians. As British journalist Robert Hardman quipped; “Not since Marie Antoinette’s immortal (if invented) remark – ‘let them eat cake’ – has there been such an ill-advised catering directive.”

But of course it wasn’t wasteful spending on champagne and caviar that led to the downfall of the Shah. Rather, it was the heavy handed suppression of Islam and the brutal tactics employed by the Shah’s government to crush political dissent. On this front the Shah relied on powerful foreign allies. In particular foreign intelligence services in the U.S., Israel and France all helped establish and train SAVAK – the Shah’s secret police force. Over the following decades SAVAK agents conducted a vast campaign of repression within Iran – coordinating censorship of the press and popular media; arresting dissidents and torturing anyone suspected of opposing the monarchy. Their emblem was the mythical lamassu. In 1977, under pressure from U.S. President Jimmy Carter and various human rights organisations, the Shah began to loosen his grip on Iranian politics – granting amnesty to some political prisoners, pledging to end the torture of political dissidents and gesturing towards the prospect of free and fair elections.

These reforms proved too little and arrived too late and, by 1979, every opposing faction within Iranian politics was calling for the abdication of the Shah. Millions of people all over the country took to the street in demonstrations that lasted for weeks. When the dust settled it was the theocrats that emerged victorious and the new constitution established the conservative cleric Ruhollah Khomeini as the country’s ‘Supreme Leader’.

In the immediate aftermath of the revolution, when hostility towards the Shah’s regime was still at boiling point, Khomeini’s right-hand man – Ayatollah Khalkhali – called upon his followers to burn down the Shah’s tent city and bulldoze the ruins at Persepolis. Thankfully, cooler heads prevailed but the regime has remained stuck in an uneasy standoff with its own cultural heritage for the last 45 years. According to the men in the black turbans all the positive aspects of Iranian society can be traced to the arrival of Mohammad and his followers in 622 A.D. This, however, is not a viewed that’s shared by the majority of Iranians – who remain quite proud of their ancient heritage.

On the way back from Persepolis Peyman took us to the monumental rock tombs at Naqsh-e Rostam5. The tombs themselves – which are thought to belong to Darius the Great and his son, Xerxes – are cut into a cliff face and are accompanied by similar reliefs to those found on the palace walls of Persepolis. Once again you can see the Emperor receiving blessings from god while much smaller figures line up underneath to offer tribute.

While the Achaemenid-era tombs dominate the cliff face the site is actually named after the smaller reliefs depicting later Sassanid kings*. Although these two empires were separated by five hundred years the addition of Sassanid inscriptions tells us that, much like the Pahlavis, the Sassanids also craved some of Cyrus’ reflected glory. The most famous of the reliefs at Naqsh-e Rostam shows the Sassanian king Shapur I, who sports an enormous afro, accepting the surrender of a Roman Emperor. This was not an episode of Roman history that I was familiar with and, as soon as I was back at our accomodation, I did a quick fact-check. Sure enough the Roman emperor Valerian was actually taken captive following the Battle of Edessa in 260 AD and according to the Roman historian Eutropius he “grew old in ignominious slavery among the Parthians [sic].”

Understandably the Roman sources for the Battle of Edessa are pretty thin and they tend to blame the outcome on foreign treachery. But the defeat at Edessa wasn’t the only humiliation inflicted on the Romans during that era. The inscription on the relief at Naqsh-e Rostam tells us that, eighteen years earlier, Shapur defeated an army led by the young Roman Emperor Gordian III (Gordian appears to have been killed during or shortly after the battle). Following that victory Shapur states that he managed to extract a massive tribute from Gordian’s successor Phillip the Arab in return for ending his campaign across Armenia. Finally, in 260, he describes his victory at Edessa where his troops faced down 70,000 Roman troops and ultimately captured the Emperor Valerian. After documenting this string of triumphs Shapur assures his audience that he also conquered lots of other places but he doesn’t want to labour the point.

We searched out for conquest many other lands, and we acquired fame for heroism, which we have not engraved here, except for the preceding. We ordered it written so that whoever comes after us may know [the] fame, heroism and power of us.

The inscription then lists, at length, all the sacred fires established by Shapur to thank Ahura-Mazda for his victories over the Romans;

Thus, for this reason, that the gods have made us their ward, and with the aid of the gods we have searched out and taken so many lands, so that in every land we have founded many Behram fires and have conferred benefices upon many magi-men, and we have magnified the cult of the gods.

And here by this inscription, we founded a fire, Khosro-Shapur by name, for our soul and to perpetuate our name, a fire called Khosro-Aduranahid by name for the soul of our daughter Aduranahid, queen of queens, to perpetuate her name, a fire called Khosro Hormizd-Ardashir by name for the soul of our son, Hormizd-Ardashir, great king of Armenia, to perpetuate his name. . .

On and on he goes inaugurating sacred fires.

1. A thousand apologies to Peyman for comparing his religion to George Lucas’ half-arsed space religion.

2. I say ‘happy’ but the only time I saw Peyman actually crack a smile was in response to a bit of gallows humour from Matt. On the way out to Persepolis we passed a veterinary hospital and, a moment later, a dead dog. ‘He almost made it’ said Matt.

3. Unlike’s Snyder’s Xerxes, the royals depicted on the relief at Apadana are both blessed with very luxurious beards.

4. You don’t have to travel all the way to Iran to see a recreation of Persepolis because the Getty Museum in Los Angeles produced this neat little interactive walkthrough to coincide with their 2022 exhibition on Ancient Persia.

5. Just to make things more confusing; the actual historical figures depicted on the reliefs were forgotten for several centuries so the site became known as the ‘Mural of Rostam’ after a mythical Persian hero.

Notes:

Martin Beglinger (2015) – The Most Expensive Party Ever

Mehdi Taheri (2023) – Persepolis Tent City in the Aftermath of the Imperial Celebration, 1971-1979

Abbas Alizadeh & Matthew W. Stolper (2019) – The Past and Present of the OI’s Work in Iran

Xenophon (370 B.C.) – Cyropaedia: The Education of Cyrus

Diodorus Siculus (45 B.C.) – Bibliotheca Historica

Warren Soward (2007) – The Inscription Of Shapur I At Naqsh-E Rustam In Fars

Roland G. Kent (1946) – The Oldest Old Persian Inscriptions

Ian Hughes (2023) – Thirteen Roman Defeats

Pedram Khosronejad (2017) – Unburied Memories: The Politics of Bodies of Sacred Defense

Leonard William King (1907) – The Sculptures and Inscription of Darius the Great on the Rock of Behistûn in Persia

Ali Ansari (2012) – Alexander the Not-So-Great: History Through Persian Eyes

Jona Lendering (2004) – Visual Guide to Persepolis

Leave a Reply