Searching For Cyrus: Part III

Rediscovering Ancient Persia in the suburbs of Yazd and the cliffs outside Kermanshah.

From Shiraz we travelled north to the desert city of Yazd which, thanks to its mud-brick architecture, felt like stepping back in time. The climate in the region is punishingly inhospitable – averaging less than 60mm of rain per year with summer temperatures routinely reaching above 40 degrees. To deal with these conditions the city is fed by an underground network of aqueducts known as qanāts. These gently sloping tunnels start in the foothills of distant mountains and feed into cisterns underneath the city. The qanāts work in tandem with another clever bit of engineering – wind-catching towers called badgir which draw cool air out of the tunnels and circulate it through homes and businesses.

By taking advantage of the low humidity, and the substantial difference between daytime and nighttime temperatures, the residents of Yazd have also been able to construct simple but effective cool rooms for preserving perishable goods and producing Persian deserts like faloodeh and sorbet. These yakhchal (lit. ‘ice houses’) are dome-shaped structures with thick walls made from a water-resistant mortar and this method of producing and storing ice has been in use for at least two and a half thousand years.

While the architecture and the hydrology of Yazd was fascinating I was more curious to see if I could find any remnants of the old Persian religion – Zoroastrianism. There’s estimated to be between 11,000 and 15,000 practising Zoroastrians living in Iran today. If you’ve never met a Zoroastrian that’s probably because there’s only about 200 thousand followers worldwide. Although the religion started in Iran most of its current adherents live in northern India where they’re still known as the ‘Parsees’. This religio-ethnic group are descended from Persians that fled Islamic persecution in the 10th Century.

You may not have heard of Zoroastrianism but some of your favourite mid-range Japanese cars and supporting characters on Star Trek are named for its god – Ahura Mazda. There’s also a thread between Christianity and Zoroastrianism because the biblical ‘magi’, who showered Mary and Joseph with impractical gifts, are thought to have been wandering Zoroastrian priests. In our current secular era Zoroastrianism’s strongest connection to pop culture is probably the late, great, Freddy Mercury (born Farrokh Bulsara) who was born into a Zoroastrian family in Zanzibar before emigrating to Britain.

The religion itself is named after its founding prophet, Zoroaster, who is thought to have lived some time in the 7th Century B.C. If you grew up following any of the Abrahamic religions (Islam, Christianity and Judaism) you’ll recognise many of the key features of Zoroastrianism. There’s a single god, a lying serpent, angels and demons and a long wait for an apocalyptic fight between good and evil – the ‘frashokereti’. Much like Muslims, Zoroastrians carry out ritual ablutions (washing) before prayers – which are also prescribed five times a day. Islamic scholars generally downplay the similarities between Islam and Zoroastrianism but it’s hard to ignore the resemblance. In his somewhat blasphemous Treatise on the Gods the American journalist H. L. Mencken points out that this sort of religious syncretism is not confined to Islam.

“It was Persian priests, or magi, who came to Bethlehem to worship the infant Jesus, as Matthew records. The Parsees of India carry on the old faith to this day. They have still further intellectualized it, but they yet maintain ceremonial fires and they yet pray on the seashore to the rising and setting sun. These Parsees are the descendants of Old Believers who refused to yield when the Calif Omar conquered Persia in the year 641 and ordered the whole populace to turn Moslem. They fled to islands in the Persian Gulf, and later on to Bombay, where they have prospered vastly. The old religion is by no means extinct in Persia itself. On the contrary, it has infected Mohammedanism, there as elsewhere, and so late as the Seventeenth Century, after a thousand years of Islam, a Persian reformer, Akbar by name, proposed formally that it be revived. He was put to death for his pains — but every Moslem, when he prays, continues to face the East whence the sun rises, just as every Christian goes to church on Sun-day, celebrates Christmas on the dies natalis solis invictus or birthday of Mithra, and employs symbols and ceremonials borrowed from the ancient sun-worship at Easter, the time of the vernal equinox. The fires that are lighted on Midsummer Eve by the peasants of most of the countries of Europe go back to the time when their barbaric ancestors, seeing the sun-god beginning to lose power, sought to offer him reinforcement. “

Just outside of Yazd are the ruins of a type of sacred site that were once common in ancient Persia – the Towers of Silence. According to Zoroastrian traditions base elements like earth and fire can be contaminated by the bodies of the dead. As such, Zoroastrians practise a funerary method known as ‘excarnation’ where the body of the deceased is left in the open to be fed on by wild dogs and vultures. This final act of charity is meant to put the departed in good stead with Ahura Mazda. After the bodies have been picked clean, designated priests collect the bones and deposit them in a pit in the centre of the tower where the remains are doused with lime to speed up their disintegration. How this process squares with the monumental tombs we’d seen at Naqsh-e Rostam is a bit of mystery.

For obvious reasons the Towers of Silence were usually constructed some distance away from towns and cities but, over time, cities like Yazd have expanded – threatening the privacy of the dead. For this and other reasons most Iranian Zoroastrians began to abandon the old funeral rites In the early 20th century – opting for burial or cremation instead. In India, where excarnation is still practised, the challenge has been finding enough birds to jumpstart the process. Widespread contamination of the food chain has decimated the vulture population in Northern India – compelling Parsees to fund captive breeding programs for vultures simply so that they can continue the traditional funeral rites.

For its part, the current Iranian regime tolerates a small remnant community of Zoroastrians – largely because they don’t proselytise and they don’t try to gather converts from the Muslim population. As a general rule, Zoroastrians tend to marry within their religious community so they’re not seen as a threat to the primacy of Islam. Contrast that with the unfortunate followers of the Baháʼí Faith – who have been considered heretics by religious authorities ever since the sect was founded.

In a recent survey on Iranaina attudies towards Religion conducted by Dutch research institute GAMAAN only one-third of respondents considered themselves to be practising Shia muslims. The majority of respondents fell into some sort of irreligious category (non-religious, atheist, agnostic etc). Most surprising of all, however, were the 8% of respondents who checked the box for Zoroastrianism – which, if it were extrapolated to the wider Iranian population, would give the religion roughly four million followers.

This is obviously not the case and, in a follow-up paper, the researchers concluded that these respondents were expressing a nationalist counteridentity rather than fraudulently claiming to worship Ahura Mazda. According to Ammar Malek and Poona Tamimi Arab:

“large swaths of the [Iranian[ population are alienated from their enforced, formal identity as Muslims. In this context, some imagine Zoroastrianism as civilizational heritage that offers an alternative. To self-identify as Zoroastrian is to say one is not whom the state wants one to be”

The central tenants of Zoroastrianism are heartwarmingly earnest – ‘good thoughts, good words and good deeds’ and the religion places a heavy emphasis on telling the truth. Zoroastrian cosmology divides the world into four key elements – fire, water, earth and air – but it’s fire that is most closely associated with the religion. Zoroastrian temples are built around a sacred fire and the faithful are invited to make offerings to keep the flame burning.

On a small street in Yazd, between a sandwich shop and a pharmacy, you’ll find one of the most sacred Zoroastrian sites – the Verahram Fire Temple. According to the priests that administer the temple the sacred fire in Yazd – known as the Atash Behram – has been kept alight, continuously, for more than 1500 years. The property where the current temple is situated doesn’t look like much from the street – just another walled compound in a city filled with walled compounds. Once you’re through the gate the temple itself is also fairly understated. There’s a tidy central courtyard with a reflecting pool surrounded by cypress and pine trees in front of a square building that looks a bit like a miniature version of the original Apadana Palace in Persepolis. Above the entrance to the temple is a relief of the faravahar – the winged figure thought to represent Ahura Mazda.

Most of the visitors to the Verahram Fire Temple are tourists who line up for a glimpse of the sacred fire – which flickers away in a bronze cauldron behind a thick glass wall. If you wait long enough you’l see a priest appear from a side-room to add a few bits of dry wood to the flame. The priests wear white smocks and face masks to preserve the purity of the flame. Each sacred fire is the product of a unique and complex ritual but the process behind the Atash Behram is the most elaborate. To make your own version of this flame you’ll need to combine sixteen different types of fire. Some, like the fire of a brick-maker or a the fire of baker should be relatively easy to come by. Others, like the fire from a lightening strike or the fire from a burning corpse, appear to be somewhat trickier.

This particular fire has supposedly been burning since 470 A.D., during the reign of the Sasanian King Peroz I. The fire was first said to have been housed at a temple in Larestan, before being relocated to the city of Aqda, where it burned for the next seven hundred years. It continued to be moved in response to various upheavals until it found its way to Yazd in 1934. Much like the sacred gas hobs that the Australian government has installed outside major war memorials I think we all voluntarily buy into the idea that these ‘eternal flames’ have been burning, uninterrupted, from the moment they were first lit but, in our heart of hearts, we allow for a bit of downtime for maintenance and unforeseen interruptions in the gas supply. I assume the same mentality applies to devout Zoroastrians when they consider the lifespan of the Atash Behram. But I might be wrong. Maybe this fire in the desert really has been constantly fed since the fall of Rome. That being the case I can’t help but look at the brazier in Yazd with the same sort of unease that I get when I watch someone adding another tile to one of those gigantic domino runs. Instead of admiring their dedication I mostly just think ‘god, I hope they don’t knock it over’.

From Isfahan to Behistun

From the mudbrick streets of Yazd we took a bus to the much larger and much more modern city of Isfahan which is renowned for its architecture and its handicrafts. Several of the city’s landmarks are listed on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites – most notably the enormous Naghsh-e Jahan Square which was set down in the 16th century by the Safavid ruler Abbas I when he decided to relocate the Persian capital. More recently the city – specifically its nuclear research centre – has made international headlines as one of the sites bombed by the U.S. Air Force at the behest of Israel – ostensibly to disrupt Iran’s somewhat mythical nuclear weapons program.

But when we visited in 2019 the city was as peaceful as could be. Water was running over the weir underneath the famous Khaju Bridge and everyone we met was incredibly welcoming and generous with their time. We could barely open a map or stare blankly at a phone for more than a few seconds before someone offered us directions. Within a few hours of our arrival we’d already met people who were more than happy to show us through Isfahan’s Grand bazaar, get us connected to Iran’s cell network and take us hiking in the hills to the city’s south. At one point Amy and I took share bikes out into the suburbs to visit some distant sights before returning to the city centre in the evening to catch an impromptu musical performance in the arches of Khaju. Even the idle youths of Isfahan were weirdly hospitable. At one point I remember walking down the street late at night when a car filled with teenagers cruised past. One of the young guys hung out the window with a big grin on his face “Welcome to Iran!” he shouted.

In terms of its cuisine Iran is, to borrow a travel writing cliche, a land of contrasts. During our time in the country we were treated to some amazing meals – usually garnished with pomegranate seeds – but we also ate a lot of very ordinary kebabs made out of meat so heavily processed it was almost a paste. These ‘koobideh’ were invariably accompanied by a bit of rice and half a raw onion. The frustrating thing was that you could find the mystery-meat kebabs anywhere in the country but the mouth-watering stews and pilafs turned out to be highly region-specific so whenever we found a dish we really liked we usually discovered that it simply wasn’t on the menu in the next town or province. The same situation applied to the bread which ranged from delicious loaves of barbari to flat sheets of lavash that looked like something you might use to package something fragile.

From Isfahan we headed further west on another bus to the mountainous city of Kermanshah which sits right in the middle of the Zagros range near Iran/Iraq border. The mountains surrounding Kermanshah are breathtaking and Amy and I, suitably inspired, decided to try to climb one of the smaller peaks at the northern end of the city. On the way we stopped in at a park built around another set of Sassanid era rock reliefs knows as Taq-e Bostan. Residents of Kermanshah were picnicking near the artificial lake or camped out on the slopes with bottles of Zam and little coal BBQs for cooking shish kebabs. I read somewhere that nudism became a trend in East Germany because it offered a way for people to protest the social restrictions placed on them by the state in a way that was still plausibly deniable. Iranians are a long way off from adopting that strategy but, on occasion, we did see women taking off their headscarfs and singing and dancing in public – neither of which are allowed under Iran’s religious ‘modesty’ laws. As tourists we were free of suspicion and were invited to join in on these little spontaneous acts of defiant joy.

But my reason for visiting Kermanshah was to see the most famous rock inscription from the Achaemenid-era which is found on a mountainside just outside the city at a place called Behistun (lit. ‘the place of god’). This mountain pass lay on what was once the main caravan route between the Babylonian and Persian capitals – thus making it a good place for a billboard.

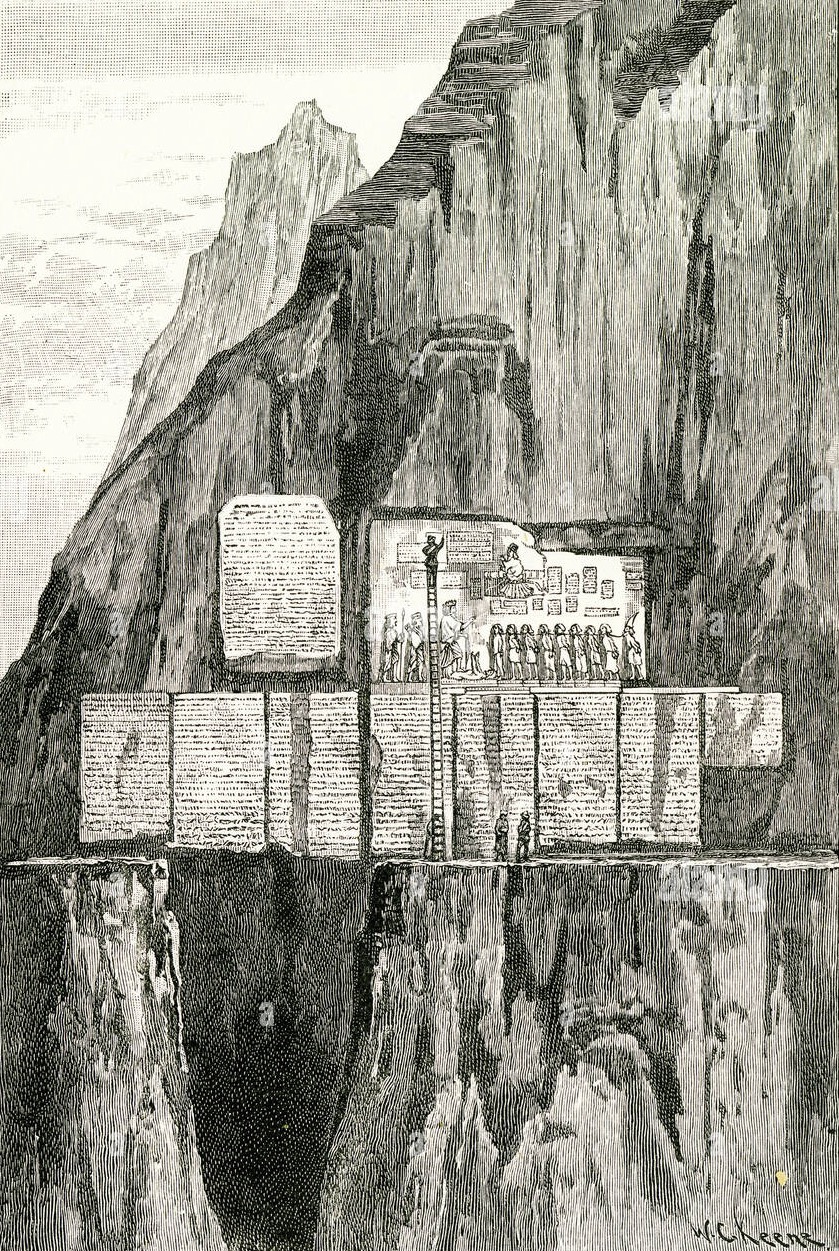

And what a billboard it is. On a limestone cliff face about a hundred meters off the ground there’s rock relief depicting Darius the Great lording over a bunch of unfortunate rebel kings. This relief is accompanied by an inscription, in three different languages, which takes up an area about the same size as a basketball court. For archeologists the story carved into the cliffs of Behistun is famous not because of its scale or because of the content of the message but because it provided the key to deciphering two of those long-lost languages.

In the first decades of the 19th century archeologists and linguists managed to decipher Old Persian cuneiform but the discovery of the trilingual inscription at Behistun allowed them to decipher ancient Elamite and Babylonian as well. Effectively the Behistun inscription did for those scripts what the Rosetta Stone did for ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics. But unlike the Rosetta Stone, which was effectively just a tax memo, the Behistun inscription recounts a very dramatic episode of Achaemenid political history. It’s a rags to riches story with bloodshed, betrayal, imposters and evil sorcerers.

Darius I commissioned the inscription sometime in the 5th century BC in order to justify his assent to the Achaemenid throne. Depending on your interpretation it’s either a sincere public-relations exercise aimed at shoring up Darius’ legitimacy or it’s a thinly veiled confession of a successful military coup designed to serve as a warning to would-be rebels. I lean towards the latter interpretation but the intended audience for the message is a bit of an open question because the Behistun Inscription is a long story written in a very small font and it’s situated halfway up a sheer cliff face. In terms of the effort and expense involved this is like bankrolling a blockbuster movie purely to restore your reputation but then screening it in the break room of an oil rig.

Setting aside the practicality of the inscription what it actually relates is the story of Darius The Legitimate Heir To The Achaemenid Empire and definitely not the story of Darius The Guy Who Killed Everyone In Line For The Throne. The inscription starts by laying out Darius’ family history going back several generations until some connection to the Achaemenid royal line can be established. This is because, inconveniently, Darius was not one of Cyrus’ sons. But, if you take the long view, like Darius does, then we’re all sort of related.

Having spent the first twenty six lines detailing what he found on ancestry.com Darius tells us that, like Cyrus and his sons, he too is descended from the mythical Achaemenes and, because our sources for this period are thin, we sort of have to take his word for it. For what it’s worth the Greek historian Herodotus (not the most reliable narrator either) insists that, before he seized power, Darius was a man ‘of no consequence’ and his biggest claim to fame was that he had served as a spear carrier for Cyrus’ son Cambyses. So, at this point, all we know is that he had access to sharp objects and he was quite close to the royal family.

So what happened to Cyrus’ actual heirs? Darius sort of glosses over the death of the older son, Cambyses who, allegedly, jabbed himself in the leg with his own sword and died of an infection. It doesn’t matter. The important thing is that he definitely wasn’t murdered by Darius. The next part of the inscription is a rambling and incoherent story detailing what happened to Cyrus’ younger son, Bardiya. Here we get Darius’ version of events which sounds like something a four year old would come up with to explain how all the crayon got on the wall.

According to Darius the real Bardiya was murdered by Zoroastrian sorcerers and replaced by someone that looked just like him. This took place when, and I quote, ‘[all] the people became evil’. So, in an effort to set things right, Darius and a few of his friends broke into the palace and killed the ‘false Bardiya’ and everyone that was protecting him. The take-home message is that it definitely wasn’t the real Bardiya and it definitely wasn’t a coup.

The next part of the inscription acknowledges the somewhat awkward fact that at least half a dozen kingdoms within the Empire broke into open rebellion the moment Darius took the throne but we’re instructed to ignore this series of events because (*checks notes*) they were all liars. Rest assured these rebellions had nothing to do with the fact that some random bodyguard had declared himself Emperor.

Much like the reliefs at Persepolis the Behistun carvings depict Darius as a larger-than-life figure when compared to all the captive rebel kings who look like little one-meter gnome people (the last of whom appears to be wearing a dunce cap). Some modifications also appear to have been made to the inscription after the fact. Darius, for example, apparently wasn’t happy with how his beard looked because that’s been replaced and stapled on later. The other addition is the last rebel king who appears to have been added some time after the others – suggesting that Darius was still dealing with rebellions long after he took the throne.

In the last part of the inscription Darius thanks Ahura Mazda for his victory over all the liars and imposters and says that he’s accomplished all sorts of other feats but he’s not going to list them ‘lest he who shall read this inscription hereafter should then hold that which has been done by me to be excessive and not believe it and take it to be Lies’. To which I say ‘No! Darius. Don’t be like that. We believe you’.

Darius was clearly not convinced that his version of events would be well received by those that came after him so he had several hundred tons of rock removed from the cliff face underneath the inscription so that no one could climb up and rewrite history. This decision certainly helped preserve the site but it did make studying the inscription a challenge for later archeologists. In particular there are some wonderful illustrations of British archeologist Sir Henry Rawlinson studying the inscription from the top of a very precariously placed ladder.

When we visited Behistun we had the place to ourselves and it was clear that the site was a somewhat neglected landmark. The entrance to the park consisted of a small parking lot and a children’s playground beside an abandoned kiosk. The approach to the inscription itself was fenced off and overgrown with weeds and there was no real signage to indicate the significance of the site. When I peered through the dusty windows of the kiosk all I could make out were a handful of little plastic Cyrus Cylinders scattered across the floor.

A few hundred meters further west of the Behistun inscription there was a slightly more poignant archeological site known as the Farhād Tarāsh. On that part of the mountain a massive stretch of cliff face has been chiselled flat. No one knows when this slab was carved but it would have been an immense undertaking at any period in history so it’s a bit of a mystery why it was left blank after all that exhaustive preparation.

Thus it stands today as an enduring monument to the age-old problem of writer’s block.

- .

Notes:

Roland G. Kent (1946) – The Oldest Old Persian Inscriptions

Behrouz Boochani (2019) – No Friend But The Mountains

Layli Foroudi (2020) – The Architecture of Heat: How We Built Before Air-Con

Mansour Shaki (1998) – Elements in Zoroastrianism

Leonard William King (1907) – The Sculptures and Inscription of Darius the Great on the Rock of Behistûn in Persia

John Paul Kleiner (2014) – Nudism, Me and Eastern Germany

Joobin Bekhrad (2018) – Iran’s Ancient Engineering Marvel

Faezeh Kazemi (2024) – The Yazd Qanat System: A Marvel of Ancient Engineering

Hareth Pochee (2018) – The Physics of Freezing at the Iranian Yakhchāl

Frantz Grenet (2013) – Remnants of Burial Practices in Ancient Iran

Ammar Malek & Poona Tamimi Arab (2020) –Iranians’ Attitudes Toward Religion

Leave a Reply